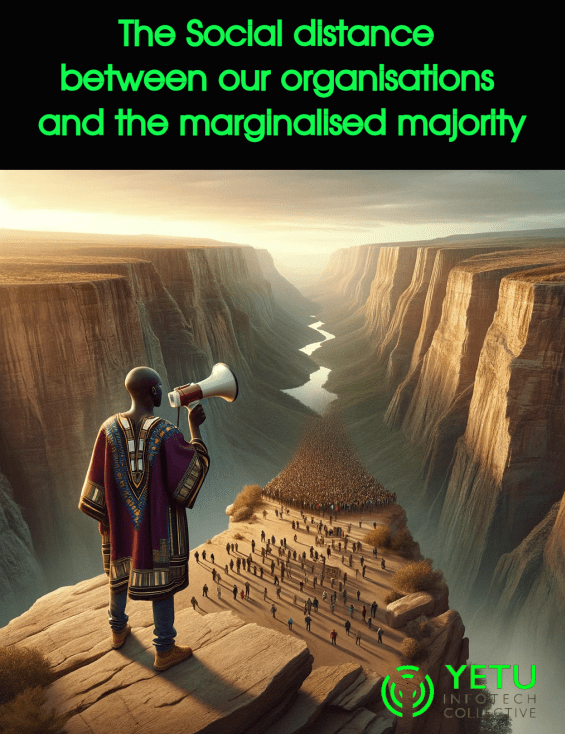

The contradictions of post-Apartheid South Africa are deepening, but progressive organisations lack the capacities to connect with and mobilise the excluded to secure a just outcome of the impasse.

This is an open-ended activist dialogue that we hope will take many forms. Please register here to receive relevant resources, get invites to gatherings,and suggest how we can deepen the reflection.

Join this critical reflection

The political moment

We see growing unemployment, poverty and violence as the political and economic elite put their interests ahead of the marginalised majority. Objectively, these conditions contain possibilities for the growth of popular resistance and progressive politics.

Despite rising discontent, there are very low levels of consciousness and organisation among the marginalised. Instead, we see increasing alienation, depression, the predominance of escapist behaviours (like religion and alcohol) and intensified competition between marginalised people for survival. We see the strengthening of reactionary ideologies like patriarchy, xenophobia, etc.

Progressive organisations are weak and fragmented. They tend to focus on single issues or work in isolated geographies. As a result of sectarian ideologies and bureaucratisation (NGOisation), they are too often inward-looking and preoccupied with their own reproduction. They tend to ‘preach to the converted’ or pander to the needs of those with power (donors, policymakers, etc).

The communication challenge

In the beginning was the word and it was recorded and distributed (controlled) by a class of priests and bureaucrats. Since the invention of the printing press access to the means of mass communication has broadened and demoralised. Today, it is estimated that 76% of people in South Africa have some access to the means to produce, share and receive content over the Internet.

Too much of the communication produced by progressive organisations is in text format (requiring literacy), in English (requiring proficiency in a colonial language), and in long form (requiring discipline and a ‘reading culture’).

When we engage a popular audience, we too often generate a power dynamic of the ‘expert/guru with great wisdom to impart’ and the ‘simple idiot with nothing but their chains to lose’. This is what Paulo Frier called the banking system of education and is antithetical to a liberatory practice.

In the name of ‘speaking truth to power’ we prioritise communication with policymakers, academic think tanks, and journalists.

Too much communication is produced for audiences of the middle-class elite and alienates the marginalised majority:

Many of us come from left-sectarian traditions and/or are NGO workers. We communicate for imagined audiences of insiders who think like us.

We “preach to the choir” with all kinds of clever formulations that use alienating language/jargon and assume a pre-existing understanding of the issues.

We urgently need to create a new mode of mass communication enabled by the advances in technology.